Eastern Germany (inc. Berlin) 2024

(Page 7 of 7 / Links to other pages at end of this page)

Day 7 – Colditz Castle and End Note to the Trip

On day 7, the final day of our brief tour around eastern Germany, we visited Colditz Castle, arriving just ahead of its opening time of 10am (note that it is closed on Mondays – always check opening times of attractions before planning a visit). After just over 5 hours there, we then headed back to Berlin Brandenburg Airport to drop off the hire car and take a late evening flight back to the UK.

Colditz Castle: A Fortress of History and Intrigue

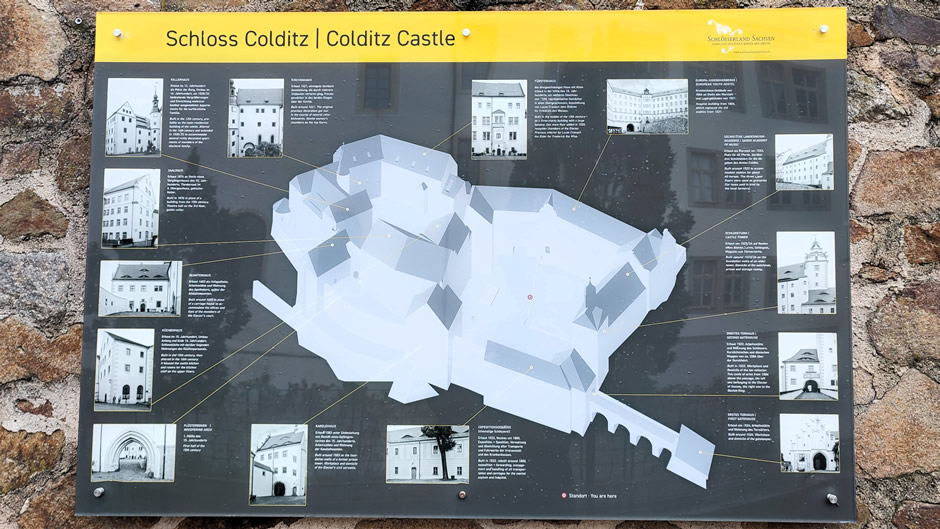

Colditz Castle, perched on a hill overlooking the town of Colditz in the German state of Saxony, is a site steeped in history and mystery. Known primarily for its role as a high-security prisoner-of-war camp during World War II and the various ways escapes were planned, Colditz Castle has become a symbol of resilience and ingenuity. Today, it offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into its storied past through interactive exhibits and guided tours.

|

|

|

|

|

The castle has a rich history dating back to the Middle Ages. The first documented settlement at the site was established in 1046 by Henry III of the Holy Roman Empire. By 1083, Henry IV encouraged Margrave Wiprecht of Groitzsch to develop the castle site further. Throughout the centuries, the site underwent several transformations. Major building works began in 1158 under Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. In 1404, the castle was sold to the Wettin rulers of Saxony. The Hussites attacked and set the castle on fire in 1430. Renovations and new constructions were ordered by Prince Ernest in 1464. A fire caused by a servant in 1504 led to significant rebuilding efforts starting in 1506. Before World War II, Colditz Castle had served various purposes, including being a royal residence for the electors of Saxony and housing one of the largest menageries in Europe during the early 16th century.

During World War II, Colditz Castle was designated for “incorrigible” prisoners who had repeatedly escaped from other camps. Despite its reputation as an escape-proof fortress, it became the site of numerous daring escape attempts. The prisoners, using their ingenuity and resourcefulness, devised elaborate plans to break free, including digging tunnels, disguising themselves, and even constructing a glider in the attic. Between 30 and 36 men successfully escaped, with many more attempts thwarted by the guards or prisoners being recaptured.

After World War II, Colditz Castle underwent several transformations. Initially, it served as a temporary holding area for German prisoners and displaced persons. As Europe began to recover from the war, the castle eventually returned to civilian use. After serving as a prison for local criminals, it was repurposed as a home for the aged and later as a nursing home, as well as a hospital and psychiatric clinic. Its use as a nursing home and hospital continued until the early 1990s. After that period, the castle was gradually restored and again repurposed, this time for tourism and historical preservation. Today, it serves as a museum and a youth hostel, attracting visitors from around the world who are interested in its rich history and the famous escape attempts during World War II.

The Visit

On arrival, we booked a guided tour and the timing meant visiting the first half of the interactive exhibition, then going on the guided tour (in English and visiting parts of the castle not included in the interactive tour – highly recommended) before returning to complete the exhibition rooms. As well as the guided tour, the multilingual interactive part of the exhibition was excellent; visitors are issued with a “HistoPad” tablet device and in each room, QR codes are scanned. The HistoPad provides a virtual tour of the castle, complete with 3D reconstructions and detailed information about the exhibits. The museum covers various aspects of the castle’s history, from its medieval origins to its role during World War II. When holding up the device and pointing it around the current room, the surroundings are re-visualised complete with furnishings and costumed people. There are plenty of objects on the tablet screen to click on and find out more about the history and escape attempts by the prisoners. As a bonus, each room has a ”hidden” escape object to collect, to help you “escape” (e.g. A hand-drawn map of the area, compass, train timetable) – fun for all ages!

The Historical Rooms of Colditz Castle (Interactive Self GUided Tour)

The rooms seen during the “HistoPad” interactive tour offer a glimpse into various eras, from the castle’s medieval origins to its infamous role during World War II as Oflag IV-C, a high-security prisoner-of-war camp for "incorrigible" Allied officers (Oflag is a former term for a German prison camp for captured enemy officers):

The Guardhouse

The guardhouse (above), a structure integral to the castle's security, witnessed numerous escape attempts during WWII. It was here that the German personnel maintained tight security measures to prevent the high-risk prisoners from escaping. Built in 1603 on the site of a former coach house, this structure, with its wooden beamed ceilings, initially served as the court pharmacy. In the 19th century, it accommodated the administrative officials of the State Asylum for the Incurably Insane, which occupied the entire castle, and it became known as the 'Officials' Quarters'. During World War II, it became the guardhouse for the German guards at the prisoner of war camp. During the postwar days of the DDR, the hospital's staff crèche was located here.

Dining Room

When the nursing home was moved in 1996, the rooms were left in their original state and simply stabilized. This preservation effort revealed traces of the castle’s rich five-century history, including Renaissance-era painted wooden ceilings. Initially, this floor featured two residential apartments for the ruler’s family, each with a bedroom and a parlour, as well as a communal dining room. During World War II, it served as living quarters for Belgian officers.

Bedchamber

Four centuries ago, this room boasted a luxurious bed adorned with ornate lathed pillars and exquisite drapes. Chamberlains slept nearby, ready to attend to their masters and mistresses at any hour. A toilet was situated in the left window bay. The remnants of the red clay ceiling date back to 1520, and around 1600, a painted green wooden ceiling with bird motifs was added beneath it. From 1946 to 1996, this entire floor served as a ward for male patients with mental disabilities. The bedchamber by the Hunting Room now stands as a testament to its former grandeur and the tales of the hunts that once took place in the surrounding forests.

The Hunting Room

The hunting room (above) recalls the castle’s history as a grand hunting lodge. Naturally, a hunting lodge required a dedicated hunting room, which was named for its various paintings of deer and boar hunts. When the interior was redesigned for the widowed Sophia von Brandenburg, the walls were decorated with exquisite Spanish leather wallpaper that complemented the bird motifs on the ceiling. Traditionally, this room was reserved for the steward or a noble court official. During the Second World War, it housed French officers.

Bedchamber by the Vestibule

Circa 1600, the bedchamber (above) boasted a luxurious oak bed, accompanied by two additional four-poster beds for court ladies or chamberlains. The room’s exquisite decor featured painted tables, elegant wardrobes, and 18 pairs of deer antlers. The wooden ceiling was masterfully painted to resemble intricate wood carvings.

Cellar House Hallway

|

|

The cellar house hallway, an integral part of the castle’s vast network of rooms and corridors, was vital during the war. It connected different sections of the castle and likely served for storage and the movement of goods. All the rooms on the same floor are accessed from here, and the neighbouring parlours are heated from this point. The curved oak door, restored in 2015, leads to the spiral staircase. The numerous layers of paint reveal that the door has been repainted 19 times over five centuries. A small room adjacent to the spiral staircase was used as a coal store in the 17th century.

Vestibule

The vestibule (above), which once provided access to the upper gallery of the castle chapel and the loge for the nobility, was originally adorned with religious art, including 40 paintings and copper engravings depicting the Passion of Jesus. An inventory from 1630 also noted the presence of wood panelling and doors painted in green and yellow. However, when the room was modified to accommodate bathrooms for the State Asylum for the Incurably Insane, these precious features were lost. The room was subsequently tiled and divided into two sections.

Above: Upper Gallery, which can be accessed from the Vestibule, overlooking the Castle Chapel.

The Castle Chapel

The Holy Trinity castle chapel is a beautiful example of Gothic architecture and a significant part of Colditz’s history. It served as a place of worship for the prisoners and is now one of the highlights of the exhibition. The chapel’s serene atmosphere provides a stark contrast to the tension and drama that unfolded within the castle walls. The castle chapel links the cellar and elector's house, and is a spiritual sanctuary that has seen over a thousand years of history. Its interior and exterior were redesigned, preserving the essence of its original architecture:

In 1504, the chapel’s inventory listed four altars, along with chalices, crucifixes, and priestly vestments. By 1584, these altars had been replaced by a heart-shaped altar crafted by Lucas Cranach the Younger. Opposite the altar was the nobility’s loge, adorned with three pearl-encrusted crucifixes and 21 paintings depicting biblical scenes and portraits of related princes. The organ, located on the north wall above the altar, was a prized instrument from Venice, celebrated for its rich tone and reportedly costing 1,000 thalers. The current whereabouts of most furnishings are unknown. However, the Cranach altar has been part of the German National Museum’s collection in Nuremberg since 1925 and remains on permanent display.

At the time of writing, there is a project to reconstruct the chapel’s organ, which in 1941, played a pivotal role in the construction of a French escape tunnel. To muffle the sounds of digging by French prisoners, the organ would fill the chapel with music. A signalling device, cleverly disguised as a mousetrap, was used to alert the diggers by turning off the light whenever silence was needed, especially during guard inspections (this ingenious device is now on display in the escape museum of the exhibition. The organ, originally built in 1850 by Friedrich Nikolaus Jahn from Dresden and later extended by Johann Kralapp from Leisnig in 1885, featured two manuals, 14 registers, and 792 pipes. It remained in use until 1945 before falling into disrepair.

Above: Part of the French Escape Tunnel seen through a glass window on the floor of the chapel.

The French escape tunnel, nicknamed “Le Métro” tunnel, was an ambitious escape attempt by the French prisoners. Starting in the clock tower, the tunnel ran under the chapel’s wooden floor. Despite being equipped with a ventilation system and a telephone network, it was discovered just six feet away from the cliff edge, making it one of the closest near-successes at Colditz.

Cranach School, c. 1550 tempera on limewood

The painting of the Last Supper, above, was probably part of the Passion cycle adorning the balustrade of the upper gallery. In 1802, the court chapel was converted into a workhouse chapel, and the painting was relocated to the orphanage chapel in Bräunsdorf near Freiberg. It adorned the altar there until, after the Peaceful Revolution in East Germany, the abandoned chapel was discovered by youngsters who vandalized the altar. Archival research in 2009 identified this as the painting’s last known location. In 1997, the Bräunsdorf pastor had taken the painting into safekeeping. It was only after an enquiry about the painting that he learned of its origin and returned it to Colditz Castle. When the restored chapel reopened in 2015, the painting was reinstated in its original location.

Escape Museum in the Bathing Chamber

The room shown in the photo above, situated above the church’s vaulted ceiling, was originally constructed in 1420 alongside the chapel as the “maidens’ chamber” for the court’s ladies. In 1540, a tin bathtub was installed. The floor remained exclusively for women until the 20th century, serving as both an infirmary and maternity ward for the asylum. During World War II, British officers resided here. In 1980, it was transformed into a dining room for the nursing home’s residents, with the front wall and fireplace design dating back to this period. Today, the former bathing chamber forms an integral part of “The Escape Museum” part of the exhibition, showcasing the creative escape attempts by POWs during WWII.

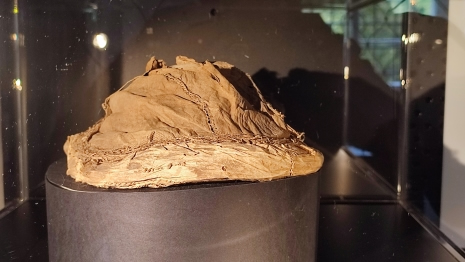

The various exhibits offer an insight into the prisoners' ingenuity; the prisoners of war at Colditz Castle ingeniously repurposed a variety of items for their escape attempts, including beds, railings, cutlery, gramophones, organ pipes, and tools. They modified their uniforms and forged identity cards. Many POWs had specialized skills: some excelled in drawing, while others were precision mechanics, tailors, or clever smugglers.

Horsemen’s Quarters

Now used to display a video as part of the exhibition, what would have been the castle’s uppermost apartment is shown above. In the 16th century, it was known as the “Horsemen’s Quarters,” providing accommodation for the Elector’s mounted noblemen. Despite its height, it even had a small kitchen for serving food. Until the 20th century, these rooms functioned as the asylum’s infirmary and maternity ward. During World War II, they were repurposed as quarters for British officers. In the East German era, the space was divided into multiple patient rooms, with one tiled wash area still preserved today.

The Attic

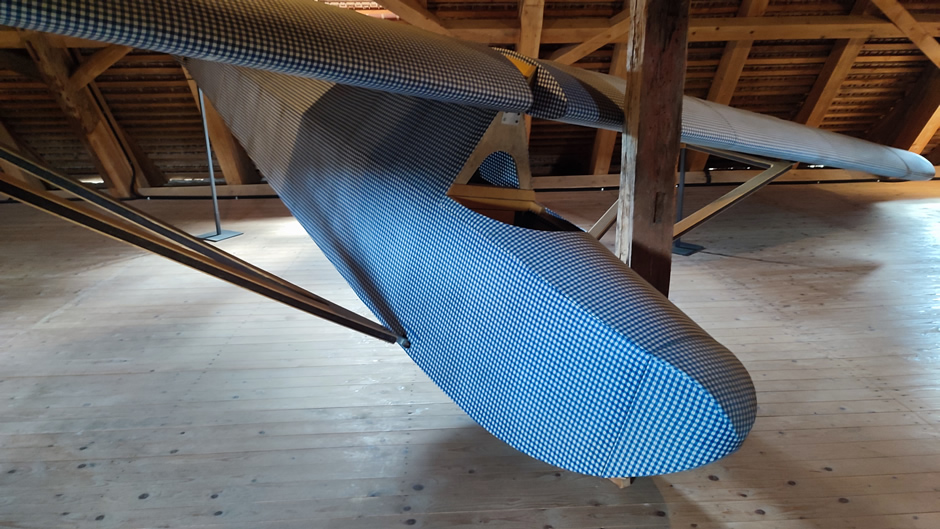

One of the most intriguing parts of the tour is the attic. For

centuries, the attic room shown above was insulated and used as a

dormitory for servants during grand hunts. However, it holds a special

place in World War II history as the construction site of the Colditz

Glider (known as the “Colditz Cock”. Construction of this glider was

perhaps one of the most audacious escape plans by the prisoners. This

space, just beneath the roof, was a secret workshop for the inmates.

British POWs secretly constructed a glider here in the upper attic,

beneath the sloping roof. Their plan, which required meticulous planning

and engineering, was to break through the gable wall overlooking the

town and launch the glider from there. The glider constructed was a

lightweight, two-seater, high wing, monoplane design and take-off was

scheduled for the spring of 1945 during an air raid blackout. However,

the plan never went through as just when the glider was approaching

completion, the American Army arrived and liberated the prisoners on 16

April 1945. The fate of the glider is not known – after World War II,

this part of Germany was in the zone controlled by the Soviets.

The glider displayed in this room is a replica, built in 2015 by a

flying club from Thuringia.

The ingenious minds behind the “Colditz Cock” glider were Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best, both RAF pilots with no prior experience in glider construction. Their unexpected ally was the Colditz Castle prison library, where Goldfinch discovered a two-volume set titled Aircraft Design by C.H. Latimer Needham. This resource provided the critical knowledge they needed. Goldfinch meticulously extracted the necessary calculations and designs from these volumes to draft the plans for the Colditz glider.

Additional insights include a sketch of the proposed catapult launch system, which was noted on the reverse of the ‘pink plan’ dated October 1944. The resourcefulness of the team was remarkable; they utilized virtually anything available within the castle. Wooden parts were crafted from floorboards, shelves, bed slats, and wardrobe doors. Metal components, such as fittings, screws, and wiring, were scavenged from the prisoners’ quarters. The glider’s fabric covering was ingeniously made from blue-and-white chequered Wehrmacht bed sheets, which were rendered airworthy by coating them in boiled oatmeal (the Wehrmacht were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945).

Above: Can you fly the glider? A simulator asks visitors to select some variables and then see where they land!

Elector’s House

The self-guided interactive exhibition concludes at the Elector's House. A significant part of the castle, it would have been used by the electors of Saxony. It stands as a reminder of the castle's importance as a royal residence during the reigns of Electors Frederick III the Wise and John the Gentle. Today, it houses a wide range of historical artefacts from Colditz Castle.

|

|

|

|

|

Construction of the Elector’s House commenced in 1470, designed as a three-storey structure. The ground floor featured a bathroom, a prison, a modest silverware chamber, and a well-lit guardroom equipped with a small armoury for the entourage. Access to the first floor was provided by a grand external staircase flanking the central entrance. During the Second World War, three rooms on the first floor were occupied by distinguished “prominent” officers, while the camp’s dentist operated his surgery in the remaining room.

|

|

Highlights of Extended Guided Tour

As mentioned earlier, the visit to the interactive exhibition described above was taken in two parts, in order to go on an extended guided tour which began at a specific time (from the ticket office). These extended guided tours of Colditz Castle offer a more in-depth look at its fascinating history, visiting areas of the castle not included in the main exhibition, as well as giving the opportunity to ask questions. There was certainly a lot of information to take in, although some of the main points and highlights follow:

The Theatre

The theatre (above) was used by the prisoners of war to stage plays, revues, and farces during their time in the castle. The prisoners performed plays such as Gaslight, The Importance of Being Ernest, The Man Who Came to Dinner, and Pygmalion. The prisoners created an original Christmas-themed ballet called Ballet Nonsense that was a big success. The ballet featured six prisoners with long hair playing ballerinas. In addition, the British prisoners put on homemade revues. During the summer months, new productions were performed every two weeks. The German garrison provided the prisoners with tools and paint for the stage sets, make-up for the actors, and attended the shows.

The theatre was used as part of a few escape attempts of varying success; A tunnel dug from underneath the stage known as the “Theatre Tunnel,” was masterminded by British prisoners. They used the cover of theatrical performances to dig the tunnel, which was carefully concealed and extended beyond the castle walls. Despite the high security and constant surveillance, the prisoners managed to dig the tunnel without being detected for a significant period. Unfortunately, the escape attempt was ultimately discovered before it could be fully executed.

|

|

Above: A hole underneath the theatre stage cut by the prisoners led into an unused corridor.

On January 5th, 1942, British Lieutenant Airey M. S. Neave and Dutch Lieutenant Anthony Luteyn escaped through the stage trapdoor and through a hole in the floor, making their way to the attic above the guardroom.

|

|

The pair marched out of the castle dressed as German soldiers. They reached Switzerland two days later. This first successful British escape was a joint British-Dutch effort (Luteyn spoke German). Neave later joined MI9 which was the British Directorate of Military Intelligence during World War II.

Solitary Confinement Cell and Guardroom

Shown above, inside the inner gatehouse, is one of many solitary confinement cells that were set up in the prisoner camp. Located to the left behind the guardroom, prisoners of war (POWs) were held in this cell for one or two weeks as punishment for disobedience, sabotage, or escape attempts. The adjacent guardroom (below) was constantly manned and fell under the jurisdiction of the guards responsible for the third castle gate.

The “Pat-Reid Cellar”

British Capt. Patrick R. Reid escaped on October 14th, 1942. He slipped through prisoner of war kitchens, climbing out of the window into the German yard, and going into the commander's office cellar. Climbing through a high window in the cellar led to outside of the courtyard of the castle. The route then led down to a dry moat through the adjacent park.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: Top left is the (former) German yard, top right is the entrance to the commander's office cellar, middle shows the window from inside the cellar and a selfless volunteer visitor demonstrating the cellar window escape from the outside, bottom photos show the dry moat and park, as seen from near the cellar window escape point.

It took Reid four days to reach Switzerland. Lieutenant Wardle escaped with Reid, whilst Commander Stephens and Major Littledale also escaped using the same route that day.

Pat Reid later wrote the book "The Colditz Story" and established the fame of Colditz Castle in Great Britain.

Colditz Castle Park

The extended guided tour continued outside the castle walls, taking a downwards path down to the park area, which was once part of a larger game reserve belonging to the castle’s estate. In medieval and early modern times, game reserves were enclosed woodlands near royal residences for keeping native game species. Colditz had up to 400 red and fallow deer, including white stags in a special enclosure. Builders’ invoices from after 1523 mention maintenance work in the reserve. Initially, the Colditz Game Reserve, first noted in 1523, was about 700 meters long, stretching from north of the castle to the Hainbach valley.

Under Elector Christian I, the Colditz game reserve was expanded in 1587 and 1590, doubling its length to two kilometres and replacing wooden fences with high walls. It featured summer houses, bridges, fish ponds, and housing for lynxes and pheasants, with access protected by gatehouses. Elector John George I further expanded it in 1624, adding a gatehouse near Zschirla. By 1600, the reserve resembled the elaborate electoral gardens in Dresden and was well-known for its High Renaissance style.

In 1800, most of the Colditz game reserve became state forestland, while the section near the castle remained under its control. When the castle was a mental hospital, this area served as a park for patients. Today, the forest area, known as Tiergarten, is open to the public at any time. The park is managed by the State Palaces, Castles and Gardens of Saxony and is accessible only via guided tours, such as this one. The view of the castle from the park is one of the best to be seen (shown nearer the top of this page).

Manhole Escape in the Park

The park area within the castle grounds provided a space for prisoners to exercise, play sports, socialize, and plan their escape attempts. It was a crucial part of their daily routine, offering a sense of normalcy and a break from the confinement of the castle. Naturally, the park was also the site of planned escapes…

|

|

Above: Drain in the park used by Dutch prisoners to escape.

Dutch Lieutenants Hans Larive and Francis Steinmetz escaped from here on August 15th, 1941 by hiding under a manhole cover in the park’s exercise enclosure. He emerged after nightfall, took a train to Gottmadingen, and reached Switzerland in three days. On the 20th of the following month, Dutch Major C. Giebel and Dutch Lieutenant O. L. Drijber also escaped using the same method as Larive and Steinmetz.

After returning to the castle from the park area, the extended guided tour concluded.

A Few Other Final Points of Note

A Building Full of Cellars

The Cellar House gets its name from the four cellars beneath it, with two dating back to the Middle Ages. You can still see the 13th-century wooden formwork in the mortar. For centuries, these cellars stored sweet Malvasia from Tyrol and Riesling from the nearby vineyard. In 1941, a hidden tunnel entrance was constructed under the castle chapel, concealed behind a camouflaged wall, with its continuation visible in the chapel.

Escape Endpoints

In September 1944, British Lieutenant Michael Sinclair became the only confirmed fatality during the escape attempts. Sinclair tried to replicate the 1941 French escape over the wire. Despite a warning from Security Officer Eggers, Sinclair was shot by the guards. A bullet struck his elbow and ricocheted through his heart. The Germans buried Sinclair in Colditz cemetery with full military honours. His casket was draped with a Union Jack flag crafted by the German guards, and he was honoured with a seven-gun salute.

Only a selection of the many escapes and escape attempts that took place are mentioned here. The Wikipedia page Here is amongst the many online resources for further reading, as are numerous books, including the classic Colditz: The Full Story, by Major Patrick Robert "Pat" Reid who, as mentioned earlier, himself was held captive and successfully escaped from Colditz Castle.

Some further photos of the castle’s exterior are shown in the thumbnail gallery below (click on an image to enlarge):

The Ticket Office

Whilst at the time of the visit, there was no café for visitors to the castle, as such, there is a (much-welcomed) coffee machine available inside the ticket office. It also sells a small selection of souvenirs and books in English (marked up prices compared with a popular online retailer that started off selling books but now sells almost everything!). Obviously, if visiting the interactive exhibition, remember to return your “HistoPad” back here afterwards and note that if you enter your email into it during the tour, you will be emailed a small gift (without spoiling the surprise, it is something that requires printing, cutting out, and sticking together).

In Conclusion

Colditz Castle is a place where history comes alive, offering visitors a unique opportunity to explore its rich and varied past. From the ingenious escape attempts of World War II prisoners to the immersive exhibits of the new interactive museum, Colditz Castle provides a captivating experience for all who visit. Its rooms each tell a unique story, echoing the echoes of history that have passed through their walls. From royal hunts to daring escapes, the castle has been a silent witness to the unfolding of human endeavours across time.

Today, it stands not only as a historical monument but also as a place of learning and remembrance, inviting visitors from around the world to explore its rich past. Whilst it is possible for visitors to take a quick stop here and admire its exterior, courtyards, or perhaps stay the night in the youth hostel here, it is well worth investing a little time (and money) touring the exhibition (with a “HistoPad”) and, if possible, also going on a guided tour to see more of the castle and its grounds. So, if you’re a history enthusiast or simply curious about this legendary fortress, Colditz Castle is a must-see destination.

End Note to the 7-Day Trip

Of course, 7 days was quite a short time to take in the sights of eastern Germany and as mentioned on the first of these 7 webpages, a number of the sites visited on this trip were associated with World War II history, something reflected in the personal interests of the author’s travel companions. That said, a lot was packed in during the week. With more time available, other highlights might have included the following, but not be limited to: More sights in Berlin (including the former West Berlin), Dresden (famous for its stunning Baroque architecture, including the Frauenkirche and the Zwinger Palace), Leipzig (a city with a rich musical heritage, home to the St. Thomas Church where Johann Sebastian Bach worked), more sights in Potsdam (e.g. the beautiful Sanssouci Palace and its gardens), Saxon Switzerland National Park (breathtaking landscapes with sandstone formations and the iconic Bastei Bridge), Erfurt (a medieval city with well-preserved architecture, including the Erfurt Cathedral and Krämerbrücke), Quedlinburg (a UNESCO World Heritage site with over 1,000 half-timbered houses), Meißen (famous for its porcelain and the stunning Albrechtsburg Castle), Chemnitz (offers a mix of industrial heritage and modern art, with attractions like the Karl Marx Monument), Görlitz (known for its well-preserved old town and as a filming location for many movies), and last but not least the city of Weimar (renowned for its rich cultural heritage, being the home of literary giants like Goethe and Schiller, and as the birthplace of the Bauhaus art movement).

And so, the part of Germany which was once East Germany during the Cold War should never be dismissed as a sightseeing destination, as it is rich in history, culture, and natural beauty.

Back to First Page (Introduction and Wünsdorf)

Previous Page (Potsdam and Nietzsche-Haus,

Naumburg)

Peenemünde and Polish Border on Baltic Sea

Rügen Island: Prora and Cape Arkona

Rostock

Berlin

Back to Top