Southwestern USA 2025 (Page 6 of 11)

Quick links to other Southwestern USA 2025 pages and/or sections Here

Los Alamos and Santa Fe

Los Alamos (Spanish: Los Álamos, “The Poplars”) is a census-designated community in Los Alamos County, New Mexico. It is historically significant as one of the principal sites where the atomic bomb was developed during World War II under the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory. The town sits atop four mesas on the Pajarito Plateau and is located about 34 miles (55km) northwest of Santa Fe.

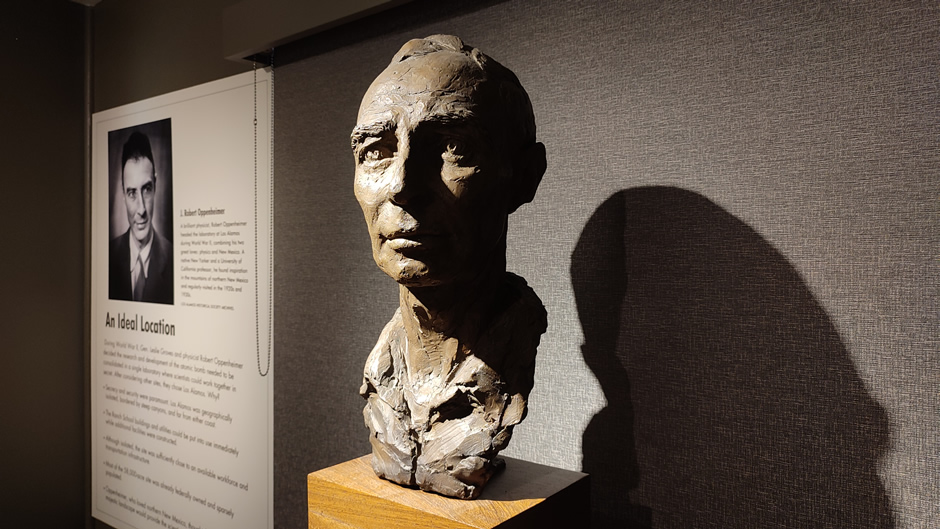

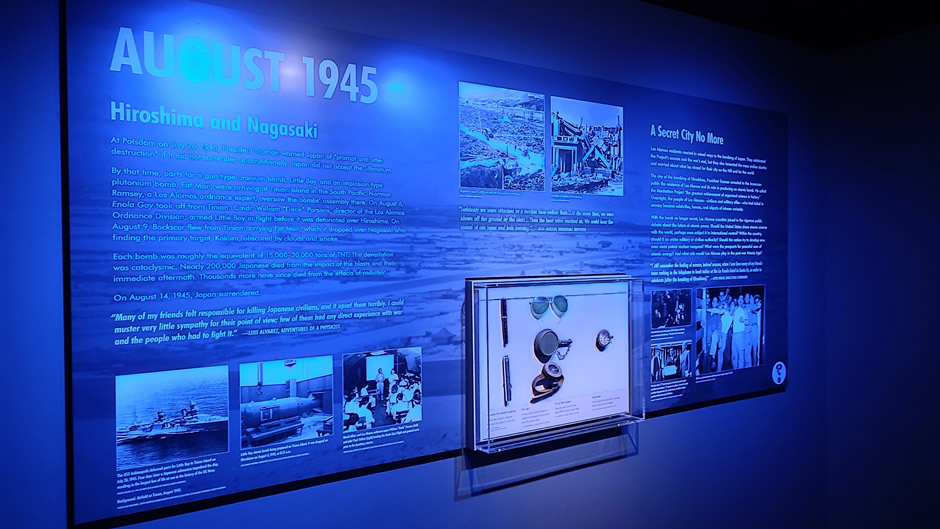

The Manhattan Project work at Los Alamos, known as Project Y, was overseen by American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and United States Army officer General Leslie Groves. Although Los Alamos became the heart of the Manhattan Project, it was also part of a larger network that included Site X at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Site W at Hanford, Washington State.

Above: About 3 miles east of Downtown Los Alamos and adjacent to the main road is the Los Alamos Project Main Gate, once the guarded entry to the “secret city”. It has been recreated at Main Gate Park, symbolising the secrecy and security of the wartime effort.

Los Alamos was selected as the site for Project Y because its remote location on the Pajarito Plateau offered natural isolation and security, while still being accessible for supplies. The existing Los Alamos Ranch School provided usable infrastructure, and the surrounding mesas and canyons created a controlled environment ideal for secrecy. Oppenheimer, familiar with the area, strongly advocated for it, believing it would attract scientists and keep them focused, while General Groves valued its potential for tight military oversight. Together, these factors made Los Alamos the ideal place to establish the laboratory where the Manhattan Project’s atomic bomb design and assembly would take shape.

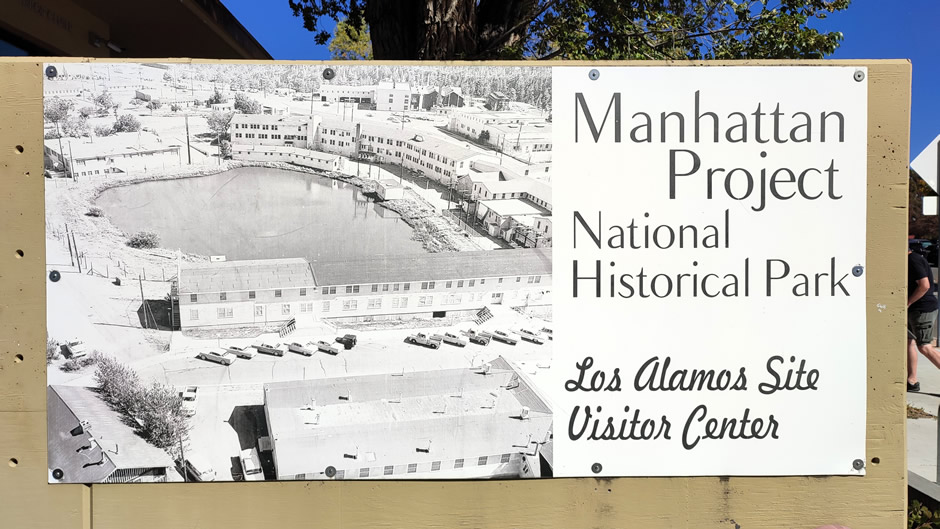

Today, the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, established in 2015, preserves this legacy across the three locations. At Los Alamos, the park encompasses 17 sites within Los Alamos National Laboratory and 13 sites in Downtown Los Alamos, reflecting both the scientific and the community life of the wartime “secret city”. Sites within the secure Los Alamos National Laboratory area (e.g. Pond Cabin, Battleship Bunker, Slotin Building, Gun Site, and V Site) are not open to the general public (a few limited guided tours are offered with tickets allocated on a “lottery-style” basis, U.S. citizens at least 18 years old only). However, visitors can explore the Downtown Los Alamos sites via a walking tour, beginning at the visitors centre next to Ashley Pond, the heart of the wartime community. The visitor centre (or “Visitor Contact Station”) provides an excellent place to ask any questions about the Manhattan Project National Historical Park and staff here are happy to guide visitors toward the historic sites. There are also walking tour maps available free of charge, as well as other informative literature to pick up. The centre also contains exhibits introducing visitors to the wartime “secret city”, highlighting the significance of Los Alamos in nuclear history.

The main sights on the walking tour follow:

Ashley Pond Park (shown below) is a central gathering place named after homesteader Ashley Pond Jr., the founder of the Los Alamos Ranch School. During the Manhattan Project, it was surrounded by key facilities and community buildings. Today it is a public park with memorials and interpretive signs. And not to be confused with the park’s namesake, the park features an actual pond that serves as a central, idyllic feature. The park remains at the heart of Downtown Los Alamos.

The Baker House (shown below) is one of the preserved wartime residences that shows how families lived during the Manhattan Project. Its architecture reflects the simple but functional style used for housing in the 1940’s. The house is part of the broader effort to conserve community structures that supported scientists and workers. It offers a glimpse into everyday life in a town built under secrecy.

The Memorial Rose Garden (below) honours those who contributed to the Manhattan Project. It is a quiet, landscaped space with plaques and plantings that commemorate individuals and groups. The garden provides a reflective pause along the walking tour. It connects the scientific achievements of Los Alamos with the human stories behind them.

The Romero Cabin (below) is one of the oldest surviving log structures in Los Alamos. Built before the Manhattan Project, it represents the area’s homesteading history. Its preservation highlights the continuity between early settlers and the wartime community. Visitors can see how local life existed before Los Alamos became a scientific hub.

The Fire Cache (below) was a stone firehouse built in the 1920s for the Los Alamos Ranch School. It stored a hand-drawn fire cart equipped with a water tank, pump, and hose, used to fight fires in an era when drought and wood-burning stoves made the campus especially vulnerable. Unthinkable today, It was constructed by local homesteader Severo Gonzales Sr. using stone taken from the nearby Ancestral Pueblo site, giving it a distinctive local character.

The Los Alamos History Museum (below) houses artefacts, photographs, and exhibits about the Manhattan Project and the town’s development. It is located in a historic building and provides context for the walking tour. Displays cover both the scientific breakthroughs and the social fabric of the wartime community. The museum is a key stop for understanding Los Alamos in depth.

Ancestral Pueblo Site (shown below): This site preserves remnants of Native American settlement on the mesa. Archaeological remains show how Pueblo peoples lived in the region centuries before the laboratory was established. It highlights the deep cultural history of Los Alamos beyond the Manhattan Project. Visitors can gain perspective on the long human presence in the area.

Site of the Big House (shown below): The Big House was the main dormitory of the Los Alamos Ranch School, then the largest building on the Pajarito Plateau, and home to students who slept year-round on unheated screened porches. It was constructed in 1917, the same year the school opened. During the Manhattan Project, it was repurposed into a shared living space housing some of the first arriving scientists and families in the rapidly built wartime community. The building also contained the site’s radio station, KRS, which was hard-wired into homes to avoid broadcasting sensitive information. The Atomic Energy Commission tore the building down in 1948.

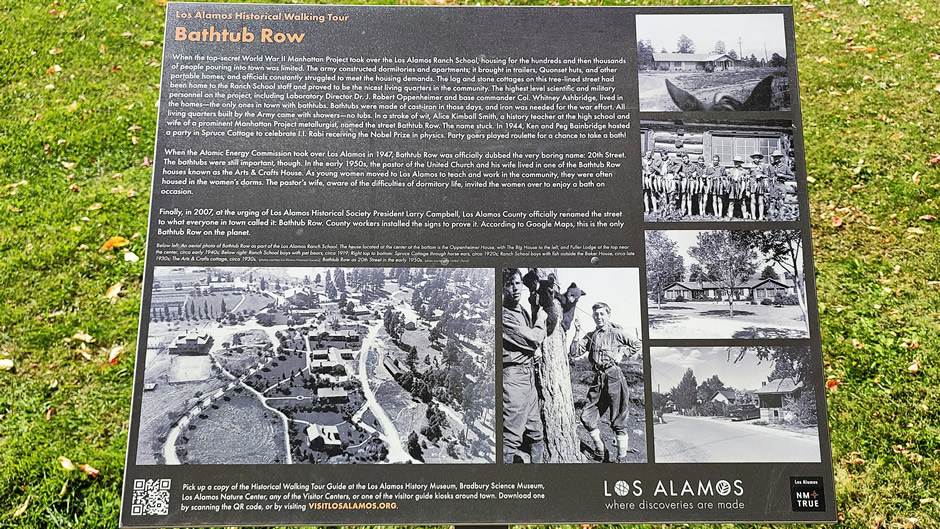

Bathtub Row is a line of historic homes which were reserved for senior staff during the Manhattan Project. The name comes from the fact that these houses had bathtubs, a rare luxury at the time. Many prominent scientists lived here, including Oppenheimer. The row remains a symbol of the hierarchy within the wartime community.

The Hans Bethe House (below) on Bathtub Row was the residence of Nobel laureate Hans Bethe, head of the Theoretical Division. Today, it is part of the Los Alamos History Museum and houses the Harold Agnew Cold War Gallery, featuring exhibits on Cold War history, scientist profiles, Nobel Prizes (like Fred Reines'), and life in the "Secret City" during that era, offering a glimpse into the Manhattan Project's legacy. The house preserves the atmosphere of the wartime era and connects visitors directly to one of the project’s leading scientists.

The Oppenheimer House (below) was home to J. Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project. It remains preserved in its original style, offering insight into his personal life. The house was not (at the time of writing) open to the public but is an important landmark, symbolising the leadership role Oppenheimer played in Los Alamos.

The Power House (below) supplied electricity to the wartime community. It was essential for laboratory operations and residential needs. The building reflects the infrastructure required to support a secret city. Its preservation highlights the practical side of the Manhattan Project.

The Ice House Memorial (below) marks the site where bomb components were stored before assembly. The original ice house was repurposed during the Manhattan Project for secure storage. The memorial explains its role in preparing the atomic bombs. It is a reminder of the logistical challenges faced by the project.

Bronze sculptures of J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves stand together in Downtown Los Alamos. They commemorate the partnership between scientific and military leadership. The statues are a popular photo stop on the walking tour. They symbolize the collaboration that defined the Manhattan Project.

Fuller Lodge (below) is a rustic log building that served as a dining hall and meeting place during the Manhattan Project. Originally built for a boys’ school, it became a central hub for community life. Many scientists and families gathered here for meals and events. Today it is preserved as a historic landmark.

The Los Alamos Post Office (shown below) played a unique role in maintaining secrecy during the Manhattan Project. For secrecy and security, residents used coded addresses instead of the town’s name. The building symbolizes the controlled communication of the wartime community. It remains an active post office today.

The Bradbury Science Museum (below) offers interactive exhibits on nuclear science, the Manhattan Project, and modern research. It is operated by Los Alamos National Laboratory. Displays include models, films, and historical artefacts. The museum connects past achievements with current scientific work. Unless anything has changes from the time of writing, it is closed on Mondays.

Manhattan Project Era Cafeteria (below): This old cafeteria is one of the preserved dining halls from the 1940’s. It served scientists, soldiers, and families during the Manhattan Project. The building reflects the everyday routines of the secret city. Its preservation adds to the understanding of community life in wartime Los Alamos.

Other not-so-central but walkable sites include a Manhattan Project Era Dormitory that housed many of the young scientists, soldiers, and staff who worked at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project, the Manhattan Project Era Chapel that provided a spiritual and communal space for residents offering a sense of normalcy in a highly secretive environment, and the Nature Center (introduces visitors to the mesas, canyons, and wildlife surrounding Los Alamos).

Today, Los Alamos National Laboratory employs around 13,000 people, working on national security, nuclear science, renewable energy, and advanced computing. It remains one of the world’s leading research institutions, carrying forward the legacy of innovation that began with the Manhattan Project.

Other attractions in and around the town include overlooks and walking trails, Planetarium & Night Sky Programmes (Astronomy events highlight Los Alamos’ clear skies and scientific heritage), the Aquatic Center, local dining and shops, and there is also an art centre in Fuller Lodge featuring exhibits and local crafts.

Introduction

Santa Fe, New Mexico, holds the distinction of being the oldest state capital in the United States and the first European settlement established west of the Mississippi River. It is also the highest state capital, sitting at an elevation of 7,000 feet. The city is located in a north-central location in the state at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. It has deep ancestral roots, with Indigenous Puebloan peoples inhabiting the area as early as 900 CE. By the 14th century, Tewa-speaking communities were established along the Rio Grande. In 1610, Spanish colonists formally founded Santa Fe, making it a key seat of Spanish, Mexican, and later American governance.

Above: Adobe-style architecture, downtown Santa Fe

Santa Fe’s history with the railroad is unusual: despite lending its name to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, the tracks never reached the city itself. This famous line, often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the largest Class 1 railroads in the United States between 1859 and 1996. The main railroad actually bypassed Santa Fe’s rugged terrain and stopped in nearby Lamy, New Mexico, with passengers continuing to the city by stagecoach and later by spur line, shaping the city’s growth while keeping its historic core largely untouched by heavy rail traffic.

Above: A market featuring Native American art and jewellery, located between La Fonda on the Plaza and Loretto Chapel in Santa Fe.

Today, the city is closely tied to art and culture, recognised as the first U.S. city named a “Creative City” by UNESCO and ranked as the nation’s third largest art market. However, the 400-year-old capital only began building its artistic reputation within the past century.

Above: The centrally-located Inn and Spa at Loretto is one of Santa Fe’s most recognisable hotels. It was built in 1975 but designed to resemble a multi-storey pueblo-style adobe village, echoing the architecture of Taos Pueblo. The author of this webpage did not stay here, but was drawn to its architecture.

The Visit

On this visit, a suitable parking lot was found near the New Mexico State Capitol, and the downtown area was explored on foot. The walk into Downtown Santa Fe highlighted the city’s distinctive blend of Pueblo and Spanish Colonial architecture, with buildings marked by adobe construction, flat roofs, and exposed wooden vigas (timber rafters). The route led to Santa Fe Plaza, the bustling heart of the city where there are various shops (including places selling Native art), restaurants specialising in New Mexican cuisine, and a variety of small cafés. This district illustrates centuries of cultural exchange, with historic structures standing alongside modern businesses, forming a compact and walkable centre. Some points of interest seen follow:

The New Mexico State Capitol (shown below), known as the Roundhouse, is the only circular state capitol in the United States. Completed in 1966, the building blends Pueblo Revival and Greek Revival styles. It houses both legislative chambers and features extensive public art collections. The building is one of eleven of the fifty state capitols in use that do not feature a dome.

Indigenous labourers under Spanish Franciscan direction. Often called the oldest church structure in the USA, the building has been repaired and rebuilt multiple times, most notably after damage during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and again in the 18th and 19th centuries, yet its adobe walls still reflect early Spanish Colonial construction methods. Inside, visitors can see a carved wooden altar screen from 1798 and other artefacts that document the chapel’s long role in Santa Fe’s religious and community history.

The De Vargas Street House (shown below), often called the Oldest House, is located in Santa Fe’s Barrio De Analco Historic District. Archaeological studies suggest parts of its adobe walls may predate Spanish colonization, making it one of the oldest structures in the country – later construction dates to the 1600s. Today, it serves as a small museum and shop.

Loretto Chapel (shown below): Constructed in 1878, this chapel is famous for its “Miraculous Staircase”, a spiral staircase built without visible supports. It’s a popular stop for visitors interested in architectural curiosities and religious history.

The Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi (shown below): Built between 1869 and 1887 under Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy, the cathedral is designed in Romanesque Revival style, contrasting with the surrounding adobe architecture. The cathedral replaced earlier adobe churches destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt and later rebuilt. Inside is La Conquistadora, the oldest Madonna statue in the United States, brought from Spain in 1625.

Santa Fe Plaza (shown below) has been the city’s cultural and civic heart since its founding in 1610. The plaza serves as a gathering place and is surrounded by shops, galleries, and historic buildings. For over 150 years, it featured the Soldiers’ Monument, an obelisk dedicated in 1868. The monument was toppled in 2020 during protests, and as of the time of the visit, no statue stands there, reflecting ongoing debates about history and representation.

The Palace of the Governors (shown behind the Santa Fe Plaza Bandstand, below) was built in 1610. This adobe structure is the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States. Today it serves as part of the New Mexico History Museum, with Native American artisans selling jewellery and crafts along its portal.

Additional notable sights around Downtown Santa Fe include the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum which houses the largest collection of her paintings, drawings, and personal items, the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, and the New Mexico Museum of Art which opened in 1917 and is noted for its Pueblo Revival architecture and collection of Southwestern art.

Above: The IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (MoCNA) in downtown Santa Fe is the nation’s leading museum dedicated exclusively to progressive work by contemporary Indigenous artists. It showcases cutting-edge exhibitions, educational programs, and a collection of more than 9,500 artworks spanning from 1962 to today (the museum opened in 1962, the same year that the Institute of American Indian Arts was founded).

Beyond the downtown area are plenty of other attractions and activities, from scenic spots and places of historic interest to cultural and artistic experiences. With this in mind, more time could have easily been spent exploring the area, suffice to say as a European visitor used to exploring cities by foot, the layout of Downtown Santa Fe had a sense of conventionality about it.

This webpage concludes with a few more photographs taken whilst walking around Santa Fe:

Link to Next Page (Page 7 of 11)

Link to Previous Page (Page 5 of 11)

Back to Top