King’s Lynn Minster (Norfolk, East of England)

Originally founded as a Benedictine Priory in 1101, the “Minster and Priory Church of St Margaret, St Mary Magdalene and all the Virgin Saints”, was only made a minster in December 2011. It is located to the south of King’s Lynn’s town centre adjacent to the Saturday Market Place. The original priory was founded by Herbert de Losinga, the first Bishop of Norwich and for 400 years, it was the monks’ home, as well as serving as the Parish Church for the town and was always simply known as St Margaret’s. It is named after St Margaret of Antioch. According to legend, she was swallowed alive by the devil in the form of a dragon. However, her holy cross irritated the innards of the dragon and it either spewed her out or, according to some accounts, the beast’s belly burst open, releasing her. St Margaret is remembered in Lynn’s Coat of Arms which incorporates three dragon heads with protruding crosses.

|

|

Originally within the parish, there were also two Chapels of Ease, which were not Parish Churches, namely St Nicholas’ Chapel to the north (web page about it Here) and St James’ Chapel to the east (later demolished). The ancient All Saints Church is the Parish Church for South Lynn. During the 19th century, St John’s Parish Church was constructed to the east, whilst the ancient Parish of St Edmund North Lynn was combined with St Margaret’s Parish. By this time, the medieval St Edmund’s Church was in ruin and St James’ Church had been demolished. St Nicholas’ is now only used for occasional services and concerts, although the three Parish Churches work together as the King’s Lynn Group Ministry.

|

|

Throughout its history, St Margaret’s has undergone many alterations and

little remains of the original Norman church. By the 13th century, most

of the original construction had been demolished and replaced by a

larger building. In the 15th century, further alterations and additions

were made and these included an octagonal central lantern and a spire

added to the top of the south-west tower. On the 8th September 1741, the

most serious damage to St Margaret's occurred during a great storm which

destroyed the spires and central lantern of the church (during the

storm, the spires of St Nicholas' Chapel were also destroyed). Despite

generous donations from George II and Robert Walpole, not enough money

was raised to be able to restore the church to its former glory. With

encouragement and support of the Borough Council, St Margaret’s Church

was granted the honorific title of King’s Lynn Minster by the Bishop of

Norwich in 2011 in recognition that it provides a ministry far wider

than that of a normal Parish Church. The minster is the civic church for

West Norfolk and regularly hosts services and events for the western

part of the Diocese of Norwich. The building is Grade I listed; its

historic and architectural significance also played a part in the

decision to make it a minster. The title of “Minster” belongs to the

building, so the parish served by it is still called the Parish of St

Margaret with St Nicholas and St Edmund, King’s Lynn.

The following

photographs show some of the highlights which can be seen during a visit

to King’s Lynn Minster, accompanied by some brief descriptive text below

each photo:

|

|

The photographs above show the west façade, which presents some different styles of English church architecture throughout the centuries. The lower section of the southwest tower, seen to the right of the main door is 12th century Norman and is marked by its intersecting arcading and buttresses with “Reed Moulding”. Moving up the tower, the middle section is 13th century Early English with plate tracery (tracery being ornamental stone openwork), whilst the upper part of the tower is 14th century Decorated Gothic and is noted for its bar tracery. The doorway, and in particular the tracery around the stained glass window above it, are in the 15th century Perpendicular Gothic style.

Another feature, which may be seen on the west façade is the Tide Clock (shown above). Often called the Moon Dial, it was originally made by Thomas Tue in 1681, to show the time of the next high tide. The clock seen today replaced Thomas Tue’s clock, which was destroyed by the aforementioned great storm of 1741. The letters around the dial read “Lynn High Tide” and the time of this was important to merchants in the town awaiting their ships. It is positioned facing the river so that the ships’ captains could also see when the next high tide would arrive. Tides follow the lunar cycle, and so the phases of the moon are shown as a bonus. A Lunar month is 29 days and 12¾ hours, and so the clock moves on 48 minutes each day (24 minutes between each high tide). There are two high tides per day, so the ‘hour’ for the high tide occurs twice each month, thus the markings on the clock represent 1-12, twice over. The time represented is in Greenwich Mean Time and the clock’s mechanism these days is powered by electricity and automatically synchronized by a GPS satellite navigation receiver.

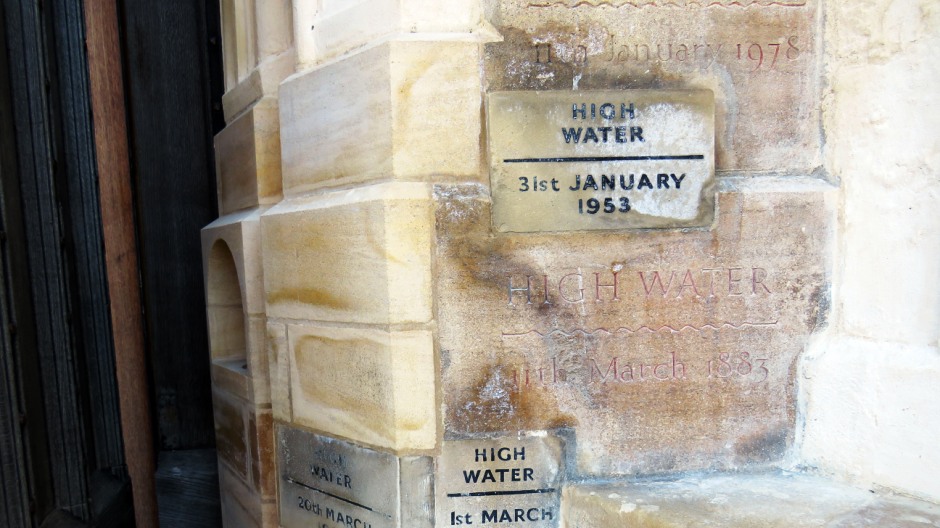

Just before entering the minster’s narthex via the main door on the western side and just to the right, may be seen a series of flood level markers. Despite the well-documented Great East Anglian Flood of 1953, the highest recorded here was the most recent to hit the building, which occurred in 1978. In more recent times, much has been spent investing in flood defences in King’s Lynn and in December 2013, a much higher surge tide occurred than the one in 1978. Although it caused much flooding and damage around the coast, the Minster was protected; the water level rose to within a few inches of the top of the gates, but was kept away by the flood defences. A marker for the 2013 flood may be seen near the gate by The Bank House Hotel, much nearer the town’s tidal River Great Ouse.

The Minster’s narthex, shown in the middle of the photo above (a narthex is an antechamber, porch, or distinct area at the western entrance of some early Christian churches), contains architecture on the north and south dating from the 12th century, and on the western side, from the 15th century. The aforementioned stained glass window on the western side dates from 1927.

|

|

At the time of the visit featured on this webpage (March, 2019), inside the Minster, access to the base of the northwest tower was blocked off due to renovation work. The tower was rebuilt in the 15th century, although its 12th century arch, matching the southwest tower shows how far it was leaning before it was rebuilt. The tower houses ten bells, seven of which are from 1766, two dating from 1893 and one, which was recast in 2005, at a time when the balls were re-hung in a new frame.

|

|

Shown above is the Minster’s north porch. It dates from the 15th century, forming the west end of the original north aisle. The 1740’s rebuilding had a narrower aisle, leaving the porch as an annexe disconnected from the nave. For many years, it was Lynn’s fire engine house and acquired the form seen today in 1914. The brick ramp, glazed screen and the window by Geoffrey Clark date from 1967.

|

|

On the other side of the narthex from the main door, heading into the Minster is the Font, which dates from 1874. Surrounding the font on the floor are hand-made encaustic tiles which were made by William Godwin in about 1870.

Just north of the font is a Hanseatic-chest, made in Gdansk in about 1420. Lynn is well known as one of the trading ports (as well as Gdansk) which were in the Hanseatic League.

|

|

Further along the northern side of the nave is the Georgian pulpit and tester (shown above, left), dating from 1745. The top part of the original “three-decker” on a Victorian base and steps can be seen. Next to the pulpit (shown above, right) is the Far Eastern Prisoners of War Association cross.

The organ in King’s Lynn Minster is of particular note on a national level and represents a landmark in the development of organ building in England. It was organ-builder John Snetzler’s first large instrument and only larger in size by his slightly bigger organ for Beverley Minster. After the great storm of 1741, the nave had been substantially rebuilt, but the organ was left unrepaired atop a screen in the church’s crossing. The Organist, Charles Burney , found the old organ to be of a very low quality and persuaded the town authorities to commission a new organ from Snetzler. Repairing the old organ would not be cost-effective, and so the new organ was commissioned at a cost of £700. It was completed in London in 1753 and installed in St Margaret’s in 1754. 100 years later, the organ was repaired and had pedals added and at the time was considered by many to be the finest in the country. St Margaret’s organ established Snetzler’s reputation as the leading organ builder of the second half of the 18th century and had become organ maker to the King. The organ case was made by Snetzler’s brother, Leonard, in the grandest Rococo style. Whilst only the façade is intact above the impost, today, it represents one of the finest 18th century organ cases around. In front of the organ is a screen, which was made in 1584, “beautified” in 1621, and placed here in 1904.

|

|

|

|

|

The above photos show the choir seating and the 13th century clerestory (the upper part of the nave, choir, and transepts of a large church, containing a series of windows). The clerestory was rebuilt around the year 1480. The perimeter seating and the parclose screens date from the 14th century (a parclose screen encloses or separates-off a chantry chapel, tomb or manorial chapel, from public areas of a church, for example from the nave or chancel). Of note here are the heads carved in the stop ends of the arch mouldings, the figures looking down from above. One of the heads in one of the capitals is of the mythological Green Man (not pictured here and information about the Green Man on an external link Here).

In front of the altar, to the left as facing it, is located a work of art called “Refugee” by Naomi Blake (shown above).

|

|

Behind the altar is the reredos (a reredos is an ornamental screen covering the wall at the back of an altar).It is by G.F. Bodley and was installed in 1899.

In front of the altar, between the choir seating is the 15th century eagle lectern. Originally richly jewelled, it has an open beak, which was used to collect “Peter’s Pence”.

|

|

The misericords (mercy seats) date from 1370 to 1377. A misericord is a small wooden structure formed on the underside of a folding seat in a church which, when the seat is folded up, acts as a shelf to support a worshipper in a partially standing-up position during long periods of prayer. There are sixteen in total and these predominately feature heads. They include on the north (shown above, left) the sons of the Black Prince and their mother, Princess Joan and on the south (shown above, right) the King Edward III, the Black Prince and Henry le Despenser (c. 1341 to 1406), whom was an English nobleman and Bishop of Norwich.

Separating the choir from the south east aisle are decorative screens. Below their arches are carved figures of “Tumblers” (acrobats).

|

|

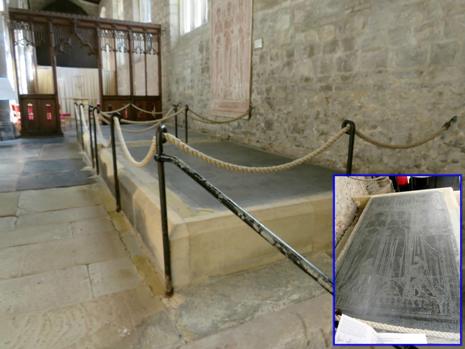

In the south east aisle are the Minster’s two impressive 14th century Great Brasses. They are the two largest memorial brasses to be found anywhere in England. It remains uncertain as to their exact origin - Flemish or German. On one of the brasses (above, left), Adam de Walsoken, who died in 1349, is shown with his wife Margaret. Adam de Walsoken is known to have owned many properties in Lynn and below their feet is a rural scene, with the earliest known representation of a windmill in England. The second brass (above, right) shows Robert Braunche, who died in 1364 with his first and second wives, Letitia and Margaret. Robert Braunche was a merchant and his will implies a riverside property. Below their feet is a Peacock Feast scene, said to commemorate the feast given for Edward III on one of his visits to Lynn, when Braunche ay Mayor of Lynn. The size and elegance of these two brasses illustrates the wealth of Lynn during the middle ages.

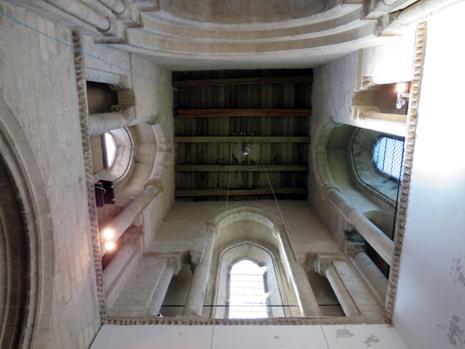

The Minster’s crossing dates from the 13th Century.

Above the arch at the eastern end of the nave can be seen the Royal Coat of Arms. It dates from 1660, but was altered during the reign of William and Mary (1689 to 1694).

The sword rest and mace stand was used to hold the civic regalia, including the King John Sword, when the Mayor attended official services.

On the nave’s front southern pew can be seen the King’s Lynn Charter Coat of Arms. It was awarded in 1974, but replaced in 1983 on the creation of the Borough of King’s Lynn & West Norfolk.

During the great storm of 1741, the spire from the southwest tower blew down, demolishing the nave between the narthex and the crossing. As mentioned earlier, the nave was rebuilt with narrower aisles and shown in the photograph above, the columns rest on the 13th century bases.

|

|

Finally, inside the southwest tower, which has arches dating from the 12th century and 13th century windows above. The globe was added and the space dedicated as the Chapel of St Edmund in memory of former Vicar, Bill Hurdman. Some more photographs of the interior and exterior of King’s Lynn Minster are shown in the thumbnail gallery below (click on an image to enlarge):

[Photos and Text: March 2019]

Back to Top